NEW BEDFORD — One Boston-based company has foreclosed on dozens of New Bedford properties over the past several years, harvesting millions of dollars in home equity that once belonged to the property owners, a New Bedford Light investigation has found.

The company, Tallage, bought property tax debt from the city and pursued foreclosure to collect on the debt. But many of the property owners lost their houses — and all the equity in them — over debts of just a few thousand dollars or less, according to The Light’s analysis of tax, property, court, and assessor records.

Tallage’s dealings have helped make New Bedford one of the top cities in the state for tax foreclosure filings, court data shows. From 2016 to 2019, when Tallage was buying the city’s tax debt, the only Massachusetts city with more tax foreclosures was Boston.

“As soon as I got a glimpse of the procedures, it blew my mind,” said Ralph Clifford, a law professor at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth who studied tax foreclosures while he clerked for the state’s land court.

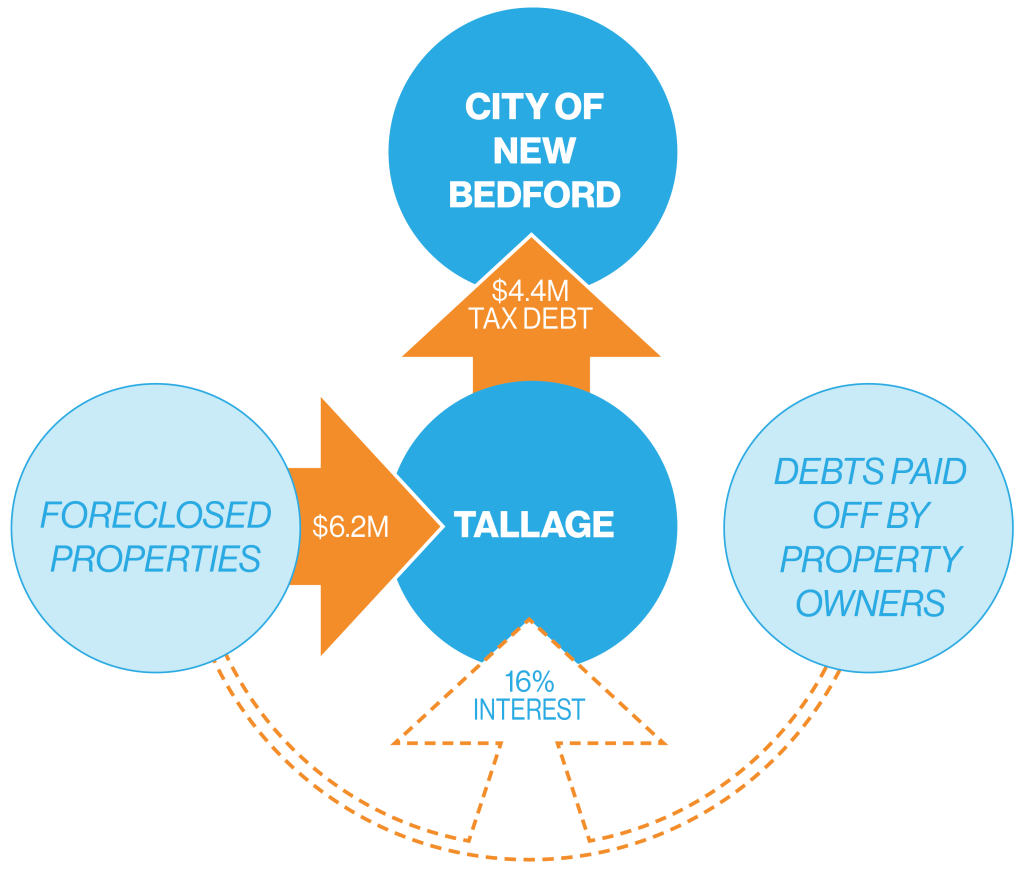

Tallage typically sold properties for less than their assessed value, but the foreclosures still secured almost $6.2 million in revenue for the company. That’s more than the roughly $4.4 million it paid for all the tax debts it bought from the city over the course of four years, records show. The company would not say how much it had to pay in legal fees and other costs associated with the foreclosures.

Proceeds from foreclosure sales aren’t Tallage’s main revenue stream. The company mainly makes money by charging property owners 16% interest on their tax debt, its founder has said. The firm does not keep statistics on the amount of money it makes on interest, according to its lawyer.

Catastrophic consequences

Tallage has foreclosed on a total of 54 New Bedford properties, property records show.

Critics call the current tax foreclosure process “home equity theft” because Massachusetts law allows cities and private tax collectors to keep all of the proceeds after the foreclosure sale — no matter the value of the home or the amount of debt. Less than a dozen other states allow for this, according to the Pacific Legal Foundation, a California-based libertarian public interest law firm.

Ralph Gants, the late former chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, described tax foreclosure as an “archaic and arcane process” in a 2020 ruling.

“[T]he complexity and opacity of this process can, and sometimes does, result in catastrophic consequences for homeowners,” Gants wrote.

Efforts to change the law have failed in both the courts and the Legislature.

“Housing is one of the most important assets that people can have, and we need to do a better job of protecting the housing,” said Jeffrey Roy, a state representative who co-sponsored a bill to reform the state’s tax law. “I just see fundamental unfairness in the way the current process works.”

Roy’s bill, which he co-sponsored with Rep. Tommy Vitolo, has failed to pass two legislative sessions in a row. But Roy says he plans to keep pushing it forward in 2023.

How a tax foreclosure happens

Most property owners that Tallage foreclosed on owed less than a tenth of the current value of their property, according to assessor data and tax records obtained by The Light.

In half-a-dozen cases, New Bedford homeowners lost properties with tax debts under $1,000. Tallage then turned around and sold the homes for as much as $212,000, property records show.

“The most common result from a [tax] foreclosure is that the original property owner is simply left with nothing,” said Joshua Polk, a Pacific Legal Foundation lawyer who has brought cases against Tallage. “They’re either made homeless, or have to make some other living arrangement, while the private investor — or municipality, in some cases — takes the property for whatever use.”

More than a thousand tax foreclosures are filed annually in Massachusetts, court data shows. In a typical year, property owners in the state lose about $56 million in equity through these foreclosures, by one study’s estimate.

Property owners rarely have a lawyer in these proceedings.

“People who are in that kind of financial trouble, where they’re about to lose their house, don’t have the money to hire a lawyer,” said UMD’s Clifford. “They’re also not, generally speaking, entitled to legal aid assistance, because they own a house. So they’re sort of in a Catch-22 in terms of getting represented.”

Polk, Clifford, and other legal scholars argue that the process violates the state and federal constitutions. The Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution is meant to prevent governments from taking property without “just compensation.” A municipality violates the amendment, they say, by keeping more than what they are owed after a foreclosure.

Clifford also raises due process concerns, saying the current tax deed procedure skips steps in the legal process that are normally required before a government can take someone’s property.

Polk says the 16% interest rate that the law allows investors to charge on unpaid taxes should already be a big enough incentive for companies like Tallage.

“The vast majority of states are able to handle their tax collection, even with private investors, without granting massive windfalls to those investors,” Polk said. “And it can be done in Massachusetts.”

From the Cape to the Berkshires

Tallage was the only bidder in the city’s four auctions. Before former New Bedford Treasurer-Collector Renee Fernandes left the city to work for Middleboro last year, she told The Light she thought Tallage faced so little competition because the city sells its debt in bulk — the city’s first auction bundled nearly $3 million in debt, and subsequent years’ bundles were in the six-figure range.

“So you have to have a lot of money,” Fernandes said.

The company describes itself as a Boston-based real estate investment firm. It’s at least partially funded by Great Elm Capital Corporation, a firm that invests in companies valued between $100 million and $2 billion, according to Securities and Exchange Commission documents.

Tallage’s name comes from a word meaning “a form of arbitrary taxation levied by kings on the towns and lands of the Crown, abolished in the 14th century,” according to the Oxford English Dictionary.

William P. Cowin is listed as Tallage’s principal. Before he registered the company in 2010, the Wharton School graduate worked for Fidelity Investments’ real estate arm, and helped underwrite and close over $1 billion in investments, according to Tallage’s website.

He also co-founded B&B Ventures, a “Boston based real estate investment company for high net worth investors.” Property records and corporate filings show that the company rents out parking spaces in a garage near Cowin’s downtown Boston condo.

That condo, a one-bedroom unit across from Boston Common currently assessed at $492,800, is the registered address for both of Cowin’s businesses.

The company’s lawyer, Daniel Hill, is one of the top lawyers in the state’s capital, according to Boston Magazine, and court records show that in 2019 he was charging the company $250 an hour for his office’s legal services.

Cowin and Hill have worked for years to build and maintain a market for their business. The company spent $142,561 to lobby Beacon Hill lawmakers on tax-related legislation over the last decade, state filings show.

Cowin himself has donated $20,350 to Massachusetts politicians since 2009, including Hill’s unsuccessful 2010 state Senate campaign. Many of his largest donations went to Democrats in the State House who have had a hand in crafting property tax legislation and don’t represent districts that include Cowin’s listed address — one comes from a district that’s closer to Albany than Boston.

Tallage has a longstanding relationship with the Massachusetts Collectors and Treasurers Association, the state’s trade association for municipal tax collectors. The company has repeatedly provided gift baskets, hosted meals, and taught lessons on how to sell tax debt at its conferences, according to the association’s website. The company has sponsored or attended at least 28 events for tax collectors since 2011, garnering numerous expressions of gratitude from the association in its newsletters.

Cowin also approaches towns directly, visiting tax collectors and select boards around the state to show them how his company can clean up their tax rolls. He tells them he has done business all over the state, “from the Cape to the Berkshires.”

The company has even bought classified ads in a trade publication for municipal employees, where it says it has worked with over 45 cities and towns.

It isn’t clear when or how Tallage’s relationship with New Bedford first began. The city had first considered selling its tax debt when Scott Lang was mayor, said Fernandes, the city’s former tax collector — but, as is often the case in government, there was “a lot of talk and never action.”

Fernandes initially told The Light that she hadn’t met Cowin until the city’s first auction in 2016, but emails obtained by The Light through a public records request show that Fernandes was in touch with Tallage by 2012.

“Just checking in on any update on a tax title auction in New Bedford?” Cowin wrote in an email to Fernandes on Sept. 26, 2012.

Fernandes replied 15 minutes later, writing, “Getting some push back from the City Council…working on it!”

After she was shown the emails, Fernandes said she “may have met Bill as early as 2012 at a state or local association meeting.”

Tallage was unable to provide details on how and when it began working with Fernandes.

Too simple

Cowin’s dealings in one town shed some light on how he markets his business. In 2017, he visited Medway, a town of about 13,000 people in Norfolk County.

Joanne Russo, the town’s treasurer-collector, had been looking for a way to get the town’s $2.7 million in delinquent taxes paid off. When she asked other nearby towns for advice, the other collectors recommended Tallage, Russo told The Light.

Russo reached out to the company, and Cowin came to Medway to walk her through the process. She couldn’t believe it at first.

“It seems too simple, because it seems like a win-win at the end of it,” she said.

The town would gather up all the tax debt it wanted to sell and hold an auction. Then, the highest bidder would pay off the town, and go about collecting the money from the taxpayers through the land court.

“We get our money, everything’s paid in full,” Russo said. “And they work, trying to do that collection.”

Court proceedings can go on for years, and they’re expensive — Tallage estimated that it costs about $2,000 to redeem each delinquent tax account. Cowin was offering what he called a “shortcut” to take that burden off the town’s shoulders.

So, Russo invited Cowin to deliver his pitch at a select board meeting in May of that year.

“The sale of tax titles is a very powerful tool to collect taxes,” Cowin told the board during his 30-minute presentation. As he explained how the debt assignment process would work, he said he could bring in at least half a million dollars for the town.

The selectmen were interested.

“We all just kind of sat back — myself, the town administrator, the selectmen,” Russo told The Light. “We’re all like, ‘Oh, this is a lot easier than we thought.’”

Later that year, the board unanimously approved a list of debts to be auctioned. On the day of the auction, to Russo’s surprise, she and Cowin were the only ones in the room. The sale was over in 10 minutes.

“It’s very, very odd,” she said, that no one aside from Tallage showed up to bid. The company didn’t face any competition at auctions in the towns of Shirley, Somerset, or Swansea either, according to news reports at the time.

Still, Russo was “very pleased” with the results. The town has held two more auctions since then, both with Tallage as the lone bidder.

Asked if she knew how many properties in the town Tallage has foreclosed on, Russo said she didn’t.

“The process afterwards really hasn’t been on my radar because it could sit out there [in land court] for three years,” she said.

Cowin has portrayed foreclosure as a rarity when promoting his services to towns.

“Well over 99% of tax titles eventually pay off, because people don’t lose their properties to delinquent property taxes,” he said at a Templeton Select Board meeting in 2014. “They just need the pressure to pay,” he said.

But property records show Tallage foreclosed on one in every 10 debts it bought from New Bedford between 2016 and 2020.

Hill, the company’s lawyer, did not dispute The Light’s research. When asked about the Templeton meeting, he wrote in an email that he did not have time to review the video, but that Cowin may have misspoke.

Cowin gave a similar statistic to the Medway Select Board a few years later. As he explained the benefits of his services, he said his company keeps tax accounts current until the debt is redeemed or foreclosed on — then, he added that “less than 0.2% actually foreclose, ultimately.”

Hill wrote in an email to The Light that Cowin wasn’t talking about Tallage’s foreclosures at the Medway Select Board meeting — instead, Hill says, Cowin was saying that under 0.2% of all taxable properties in Massachusetts go into tax foreclosure every year.

Fernandes, New Bedford’s former tax collector, didn’t know how many foreclosures Tallage had done in her city, but she wasn’t surprised when told how many there had been. She acknowledged that, as a private company, Tallage has the resources and incentive to go after delinquent taxes more forcefully.

“I think the difference is that, that’s his business,” Fernandes said.

Sign up for our free newsletter

Private investors are more aggressive in pursuing foreclosures than cities and towns are, according to Clifford, the law professor who studied tax foreclosure filings.

“The commercial entities don’t accommodate, they just want their money,” Clifford said. “It does make a difference in terms of how easy it is to settle cases in an appropriate way, or an easier way.”

Municipalities have political incentives to be more accommodating to constituents, Clifford said. Meanwhile, Tallage doesn’t have to worry about getting reelected.

“What we do, if we’re the winning bidder, we throw them all in land court,” Cowin told the Medway selectmen in 2017. “If they weren’t going to pay you, they aren’t going to pay us until they get a notice from the land court.”

For Fernandes, selling the city’s tax debt was a matter of making sure everyone was paying their fair share. She said she was happy with what Tallage has done in New Bedford — the first auction made a “good bit of money” for the city. Tallage’s winning bid amounted to almost $3 million.

“When you’re delinquent on your taxes, everybody else is paying your way,” she said. “You’re getting away with something.”

When Fernandes was asked if she thought the law should change so that property owners can keep their equity, then-city spokesperson Mike Lawrence jumped in, calling it a “speculative question.”

“It’s not up to me,” Fernandes said.

New Bedford hasn’t sold debt to Tallage since 2019. The city put a pause on aggressive tax collection during the pandemic and currently has no plans for another auction, according to the mayor’s chief of staff, Neil Mello. Meanwhile, Tallage secured 11 foreclosure judgments in New Bedford since the start of the pandemic, collecting on the debt it had already bought.

Losing everything

In the case of Deborah Foss, she didn’t know what was happening until it was too late.

The retired grandmother had spent $168,500 — the sum of her life savings and the inheritance from her late mother — to buy a two-family house on Valentine Street in New Bedford in 2015. She hoped that renting out the other unit would keep her afloat, supplementing her fixed income.

But a few years later, a deputy sheriff brought her a letter. Foss had fallen behind on her property taxes after running into health problems in 2016, and Tallage had bought her debt. The letter said the company had started foreclosure proceedings to satisfy the debt.

Foss asked the court to put her on a payment plan and give her time to sell the house so she could pay the debt and save her equity. But her written response was deemed invalid because it wasn’t filed by a lawyer, and she couldn’t afford one.

The land court approved the foreclosure. It was Tallage’s house now. Foss said she didn’t even know about the judgment until she got eviction notices in the mail.

“I was like, ‘What the hell are they talking about, eviction? I own this house,’” she said.

It was cold outside and Foss says she was sick with COVID-19 when Tallage evicted her from her home last winter. Her wife, sister, and cats were removed along with her. Over the following months, Foss would shiver and sweat as she slept in her car.

“It’s terrible, the feeling of losing everything, and not knowing,” she said. “It was all done so sneakily.”

You can help keep The Light shining with your support.

Tallage disputes Foss’s account. In a September press release, the company said she had accrued over $26,000 in tax debt by 2021 and she made no attempt to pay it off, even though she could have sold the home or taken out a loan backed by a mortgage on the house. Foss has said she didn’t know what her rights or options were once the tax taking was issued.

The company also said in the press release that they spent $80,000 to clean up an oil spill in the house’s basement.

Within a month of the eviction, Tallage sold the house to a property developer for $242,000. Foss didn’t receive a penny of the proceeds, even though Tallage had bought her debt for only $9,516.

That’s why she sued the company, with pro bono help from the Pacific Legal Foundation. In the end, she and the company reached an $85,000 settlement in August, returning about half of the money she had initially invested in the house.

Early in the settlement negotiations, Tallage tried to get Foss to sign non-disclosure agreements that would have kept her and her lawyers from talking about the case or saying anything negative about the company.

“I was like, ‘There’s no way I’m gonna do that,’” she told The Light. Her final settlement allows her to speak freely about the case.

It’s not the first time Tallage has settled with a Massachusetts property owner they foreclosed on.

In a 2021 lawsuit, a Dartmouth family represented by the Pacific Legal Foundation had sued Tallage after losing their home to a tax foreclosure. The foundation’s lawyers told The Light they could not comment on that case. When asked if Tallage had ever used non-disclosure agreements in its settlements, Hill declined to comment.

Foss had hoped her lawsuit would result in a judge striking down the law that allows Tallage to keep all the proceeds after a foreclosure sale — the Pacific Legal Foundation had success with a similar lawsuit in Michigan. But that kind of litigation would have taken months.

“I just didn’t have a choice,” she said. “I couldn’t stay on the streets any longer — I couldn’t live in my car any longer.”

The endgame

The end of Foss’s lawsuit left efforts to change Massachusetts tax law in limbo. Because the case ended in a settlement, a Massachusetts judge couldn’t issue a ruling on the constitutionality of the law.

But this month, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear one of the Pacific Legal Foundation’s equity theft cases brought by a woman from Minnesota. The federal justices will be able to decide whether a similar tax law in that state violated the woman’s Constitutional rights.

Polk, one of Foss’s lawyers, said the foundation’s “endgame” is to have statutes allowing for “home equity theft” struck down.

“This is not about protecting scofflaws from their duty to pay taxes,” he said. “This is about protecting homeowners, property owners — a lot of them vulnerable people — from really predatory practices in this state.”

The Massachusetts Legislature could also amend the state’s law, but a bill that would have made the changes the foundation is seeking has failed to pass two sessions in a row.

State Representatives Jeffrey Roy (D-Franklin) and Tommy Vitolo (D-Brookline) introduced the bill in January 2021 after hearing about a family in Easton that lost their house to Tallage. The bill would have made tax foreclosures more like mortgage foreclosures, so homeowners could keep their remaining equity after the foreclosure sale. It also would have helped make sure homeowners are informed about foreclosure proceedings before they happen.

The bill hasn’t passed because the Committee on Revenue wanted to study it more, Roy said. He and Vitolo introduced the bill again in the new session, but he couldn’t make any promises that it would actually make it through the Legislature in 2023.

“There is no ‘clear path’ when you’re talking about legislation,” Roy said. “But I think there’s a greater understanding of what the issues are, and that always increases the likelihood that we’ll be able to get something done.”

Meanwhile, Foss has used some of her settlement money to get an apartment in Fall River, and she said she plans to put the rest of it toward buying another house. But she’s still angry at the system that has deprived dozens of others of their equity while granting windfalls to Tallage.

“It’s just a bunch of rich people getting richer, and the poor people getting poorer,” she said. “And this is how it’s done.”

Email Grace Ferguson at gferguson@newbedfordlight.org.

.2309210640569.jpeg)